Between the Hedges on 9/11 - The Insider Story of the Georgia Bulldogs on September 11th

DON’T MISS OUT: Get our insider newsletter today!

Audrey Williams was trying to figure out what to do next. Explosions and chaos surrounded her inside the World Trade Center in Manhattan. Two planes had hit the Twin Towers, and eventually, buildings collapsed to the ground.

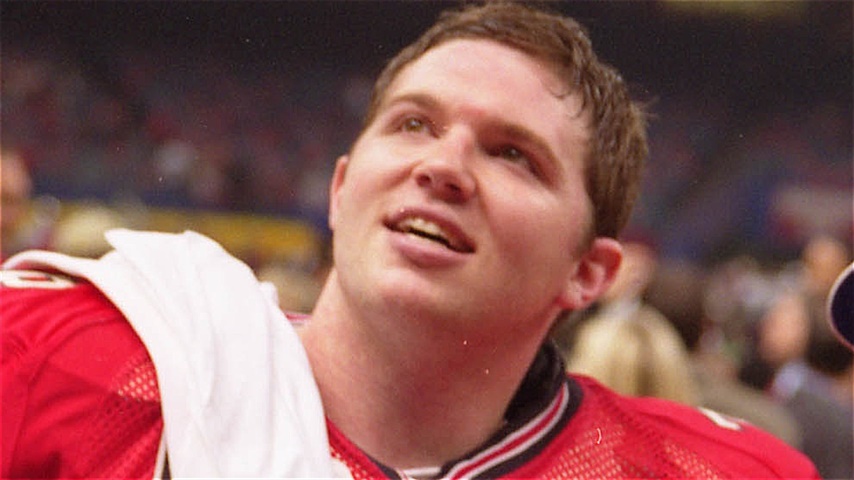

Williams’ nephew, Georgia running back Verron Haynes, and his teammates were doing their best to move past a gut-wrenching 14-9 home loss to No. 21 South Carolina three days before the most memorable Tuesday in American history.

New York City is hours away from Athens, but the events of that day brought Americans together by television, confusion, prayer, concern and eventually resolve.

That day changed the course of history, but it started like any other weekday inside of Butts-Mehre Heritage Hall for first-year football coach Mark Richt. A lot of decisions had to be made about the upcoming game against Houston. Would true freshman D.J. Shockley burn his redshirt against the Cougars? Could Richt get SEC officials to be more lenient about his offenses playing at a fast pace? Who did Georgia need to target for the 2002 and 2003 recruiting classes?

It was a normal Tuesday in Athens.

That day in the football offices started with staff meetings. Richt would have to deal with the regularly held weekly press conference at noon; Practice would conclude the day. Right on time, about 8:50 AM, the Georgia staff broke from their morning meeting, and someone rolled in a TV for Richt and a few others to watch videos of prospects on tape.

“This was back in the day when you had the TV on top a roller cart like you used to see in high schools,” Richt said. “We were getting ready to pop in the tape, and we turned TV on. We didn’t have sound on. We don’t watch recruiting videos with sound. So, we weren’t really hearing what was going on. We just saw the image. Before it went to the VHS, we saw what looked like a movie or something. One of the buildings had already been hit - smoke was coming out. Then the second plane hit live on TV.”

9/11 had begun, and what was next was impossible to know.

“When we saw (the second plane hit) we realized it was real, and not just a movie,” Richt said.

Reviewing possible incoming kickers was out of the question - confusion and shock had set in, and not just for the coaching staff.

“It dawned on me that my aunt was in that building,” Haynes said. "Mom was trying to call her sister, and no one could get through. There were no communications.”

In New York City, former Georgia running back Scott Ghedine was at Penn Station only miles from the World Trade Center watching the events unfold.

"We were gathered around small monitors," he remembered. "We all said the same thing: ‘It’s a beautiful day, how could a pilot make such an error? It was probably a small plane, and the pilot had a heart attack.' No one expected terrorism."

Back in Athens, word was spreading around campus, and everyone was rushing to any television they could find at a time when cell phones did not come equipped with social media networks embedded. 2001 was still an analog world, and television was the biggest medium.

“Everyone immediately went to the TV,” running back Musa Smith remembered. “I was thinking of my family members in the New York area. Everyone was glued to the TV. I remember it pretty stinking well. It was very shocking.”

“There was a TV, and everyone was stopped,” Haynes said of the first time he witnessed the attack on a screen. “I was like ‘What is going on?’ I was reading the ticker, and it read: ‘The Twin Towers got hit.’ It seemed like time had stopped. It was a surreal moment. It was devastating. We were under attack.”

Haynes grew up in Coop City, a housing cooperative with 35 high-rise buildings in the northern part of the Bronx. He was very much a New Yorker at the time, and his accent is still thick today. He said that he was worried for his family once he saw the images.

“I remember walking into the Butts-Mehre and turning on the TV, and you could see the plane hitting the building,” former Georgia receiver Terrence Edwards said. “I was lost at first. I'm from the South. I had never been to New York. I didn’t know where the Twin Towers were. I think most of the team was that way. It was a confusing time for everybody. But it was still unbelievable to see a plane fly into a building.”

“(UGA offensive lineman) Brady Pate had spent the night on our couch. He told us there had been an explosion in New York,” former Georgia offensive lineman Jon Stinchcomb said. “We were like: ‘What?’ We are watching it on TV. I’m about to go to class, and we watched the second plane hit the tower. I didn’t know what it was. I thought it was an explosion in a building. I didn’t see the actual plane. I saw the explosion of the Tower. What could have caused that? At the time I didn’t know it was the second plane. I had to leave to go to class while it was all still unfolding.”

The buses on campus at UGA were still running. Classes were still being held. Some students had witnessed the events on TV. Others were just waking up to the terror.

“Everyone had the same thought - disbelief,” Richt said. “When the first one happened, we, again, we thought it was a movie or something. It didn’t click. Then, when we knew it was real, we were like ‘This is something that is really bad.’”

Those images have been seared into the minds of Americans ever since. This is the story of September the 11th at Georgia. The Dawgs were under the leadership of first-year head coach Mark Richt. He inherited a talented group of players with widespread backgrounds, faiths and hometowns.

America would never be the same after 9/11. And Richt, athletic director Vince Dooley, UGA and the SEC were trying to navigate something the world had never seen. Would there be football that weekend? Would there be football that year? Was Georgia safe enough to practice that day? What was the right thing to do?

There would be far more questions than answers, and sometimes answers led to more questions. Some answers were painful. Multiple players on the team had family in New York City. Haynes didn’t know the whereabouts of family members that worked at the Twin Towers.

“HOW DO WE HANDLE THIS?”

After the South Tower was hit by United Flight 175 it was obvious the United States was under attack. What was unclear was how widespread the attacks on the country would be. Planes were being ordered to land. Lieutenant Heather “Lucky” Penney was prepared to ram her F-16 into United Airlines Flight 93 to prevent a fourth plane from striking a target that day.

All of this was unfolding as Georgia and the SEC were trying to get a grasp on the situation on the ground.

Southeastern Conference commissioner Roy Kramer was in his office at the headquarters of the league in Birmingham when he got news of the attacks. The league was getting ready for two of the biggest games of the season that weekend: Auburn-LSU and Florida-Tennessee.

“The staff joined (commissioner Kramer) to follow the events of the day to find out what had happened and then how the Conference was going to manage games of the weekend,” SEC Executive Associate Commissioner Mark Womack said of that day.

In Athens, Georgia officials decided to move forward with the press conference for that week’s Houston game.

“We debated quickly about the press conference. We decided to have it because in those days a lot of media were coming from out of town, and they were already here or close to being here,” UGA Senior Associate Athletic Director Claude Felton said. “If we had not had the press conference everyone would have been wanting comments from Coach Richt and Coach Dooley. From that standpoint, it was probably good to go ahead and do it. Otherwise, we would have been scrambling around to get comments from everyone.”

This was a time before even e-mail lists were cultivated to get the word out to a large group of people.

“In those days you almost had to talk with people individually,” Felton said.

Noon was approaching, but Richt and his staff had one eye on the TV at all times. He was trying to figure out what the appropriate move was next. Richt had been the head coach at Georgia for about nine months, but there was nothing in his decades of work as an assistant coach to prepare him for this situation.

“I don’t exactly remember what we did next. I think everyone just stayed glued to the TV, and the world kind of stopped for everybody,” Richt said. “We were trying to gather as much information as we could gather. Immediately you start thinking: ‘Should we practice today? Should we not practice today? What is the SEC going to do? Are we going to play? Are we not going to play?’”

“We go to the first team meeting, and you are trying to figure out what is happening,” Stinchcomb said. “Are we going to play? What are the implications? Is there more to the story? Was this the start to other attacks? There was so much unknown in that whole deal.”

Everyone seemed to be in the same boat: A million questions - zero answers.

The second floor of Georgia’s Butts-Mehre has offices that wrap around a conference room in the middle. Richt’s office was footsteps from that area. He was trying to figure out what to do next. The answers were not coming quickly, even if the tragedy of the day had become clear.

“All of those questions came to mind hours after you are trying to wrap your arms around what happened knowing that something truly sick - and truly significant happened. Football … everyone has a job to do, and you wonder how it affects your job,” Richt said. “How will this affect our lives? Folks were very concerned about what was going on with the country. We didn’t know if there was more to come. You started thinking about everything but football.”

Georgia’s players were scattered across UGA’s massive 767-acre campus. Eventually, the team gathered at the team meeting room on the first floor of Butts-Mehre.

"The coaches tried to keep it as normal as possible,” Smith remembered. “We were still trying to achieve our goals for the season.”

Decades later memories are hazy about what happened that Tuesday in terms of practice. Several players and coaches were not certain if the Bulldogs practiced that Tuesday, but most felt like they did. Some were certain they practiced that Tuesday. That should be noted that in reporting for this story, and it goes to show where everyone’s minds were on that day.

“If you were to pin me to it, I would say we practiced,” Stinchcomb said.

“Practice was eerie,” said Smith, who was confident in saying the Bulldogs practiced that Tuesday. “We went through practice, but the attacks were at the front of your mind. Everything else shut down, but we were practicing. I was just thinking about everyone in New York. I have family in the city. And you never know where an individual is at one time.”

He wasn’t the only one.

“My head wasn’t all the way there. I was thinking about my family,” Haynes said. “I wanted to know if anyone had gotten ahold of my aunts. I felt distraught. I felt very devastated. It was a terrorist attack. And then the uncertainty of not knowing if my family was OK.”

Smith added: "We were blessed that no one in our family was hurt, but we had a lot of friends (who were affected by 9/11). It was nerve-racking not only as an American, but as a Muslim in this country.”

Smith’s faith put him in an unenviable position. Followers of Islam, like Smith, were being blamed for the acts of others.

“You know that there are radicals out there that are going to do something stupid like 9/11 and folks are going to lash out to people who have lived humbly. That stuff happens. It happens all of the time in America,” he said looking back. “That's stupidity and ignorance. A certain group of individuals ruined it for a lot of good people.”

“I remember Musa facing criticism. That was a scary deal. I think he went through a lot more than we realized. I am sure it affected him,” Stinchcomb said. “I think he faced scrutiny and skepticism because of it. I would be shocked if it didn’t have some sort of effect on him. Mentally, Musa is tough. He’s a tough dude, but still. He was in the minority faith-wise in a time where it was the opposite of being popular.”

As practice ended, Richt called the team up to talk with them on Georgia’s Woodruff Practice Fields.

“I remember after that practice Coach Richt and a lot of people of faith - we all prayed,” Smith said. “I think he asked if anyone had family members in New York City. And we just prayed, man. We just prayed. It was not a normal practice.”

Normal was gone in America. What was not known was when the country would move forward.

“The question was if we were going to play that week, and I don’t remember how long it took for the SEC to say. It wasn’t right away,” Richt said.

After the Dawgs wrapped up for the day, Richt headed home. He was raising four children with his wife Katherine, and the duo tried to not have the TV on until the children went to bed. After 9/11, that became of particular importance.

“When you turned the TV on it was on every channel,” Richt said. “There were images of people jumping out of windows.”

"The TV didn’t come on in our house while the children were awake,” said Katherine, who learned of the attacks just after a bible study she was at Tuesday morning. “We just didn’t watch the TV unless it was football.”

She added about the visuals of 9/11 on TV: “We didn’t want them having nightmares about it.”

Katherine said that she didn’t remember what she and Mark told their children that night about the attacks.

“I am sure we talked with them about it, but I don’t recall what we said. I don't remember feeling any fear. I don’t remember feeling scared for our kids,” she said. “The concentration was on the people in the towers and elsewhere that got killed.”

"After the towers came down we started walking downtown to (in our minds) help remove rubble and find survivors,” Ghedine said. “They wouldn’t let us below 14th Street. We had no idea the magnitude of just how much destruction was down there. So then we headed to a midtown blood donation line. After about an hour they turned us away because they didn’t need any more blood. We asked how could you not need anymore? They said because no one was coming for it. There would be no injured survivors. Just deceased or straight out survivors. That hit us all hard."

By Wednesday, it appeared the SEC would move forward with games scheduled to be played on September 15, 2001.

“When the SEC said we were going to play, and we started practicing there were a few parents that didn’t agree with that - they didn’t think we should practice,” Richt said. “They considered pulling their kid out of practice, and I told them: ‘If that’s what you choose to do, I am not going to hold it against you.’”

Still, Richt and company needed to start preparing quarterback D.J. Shockley to make his first appearance in Silver Britches.

“We had planned on playing D.J. in the Houston game that week,” Richt said. “Our plan was to play him that year and give him experience. I don’t know if Shockley knew our plans or not, but our plans were to play him in the Houston game.”

Edwards was ready to play another game. The 14-9 loss to the Gamecocks was what he described as “the worst game I had played in college.” He was ready to get back to playing, but it was complicated.

“As a player, you want to get back out there the next week to rectify what you put on tape the week before,” he said. “I do remember that at first there was talk that we were going to play, and there was a lot of mixed feelings about it. I do know that there was a split. I remember a strength and conditioning coach being adamant about not playing. But as 18-year-old kids, we wanted to play - that’s what we do. I don’t think, really, any of us knew the magnitude of what was going on until more and more information came out.”

“For the team, I would say the majority of the team felt like it would be good for our country, and good for us if we were to continue to play,” Stinchcomb added.

Meanwhile, NFL executives and owners were meeting to discuss their path forward. The Jets and the Giants, both very meaningful for the New York community, had players like Vinny Testaverde who said they would not play in a game the weekend after 9/11. The governor of New York, George Pataki, told NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue that the league should not play.

Understandably, New York was the center of a lot of the decisions being made around things in the country at the time.

By practice on Wednesday Haynes still didn’t know what was happening with his aunt that went to work on September 11, 2001 in the World Trade Center.

“Verron Haynes had a lot of his family living in New York,” Felton said. “There was some attention on Verron because he had family up there. It took a while for him to get a hold of everyone and know that they were OK.”

Parents of players were voicing their concerns to Richt, too.

“What happens is you try to manage what you say to the players,” Richt said. “You had players’ parents calling - ‘What are we going to do? Are you going to practice? Are you going to play a game?’ We didn’t know. We were waiting for the SEC to make a decision. We tried to stay in a state of readiness in case they decided that we were playing.”

It was getting late in the week, and finally, the league made a decision.

“By Wednesday there was speculation - are we going to play the game or not? Later that day the SEC decided to play the games,” Felton said. “They said: 'We need to get back to normal. We need to try to make things normal.' So, the SEC decided the games were on. At practice on Wednesday, when they announced that we were playing the game, all the team was excited. They were for it. Everything really perked up.”

“A lot of times it is therapeutic, instead of sitting and fretting, to get moving again,” Richt added. “If someone was going to target a place it probably wasn’t Athens.”

Stinchcomb remembered: “Coach Richt said: ‘Part of what we can do is continue on with our lives and not let the terrorists win.’ What good does it do if we as a team don’t play? Why are we not playing? Why are we allowing them not only to destroy those buildings, but our sense of security and lives?”

“I thought we shouldn’t play,” Haynes said. “Time stopped. D-Day and Pearl Harbor were big days for the US, but this was one of the most devastating days in history. It was both towers, too, not just one. A lot happened that day. And we didn’t know what was next. I remember praying a bunch.”

Still, it looked like Georgia would host Houston in three days.

THE OVERNIGHT CHANGE OF HEART

By Wednesday night Tagliabue knew that he would recommend that the NFL not play. A day later professional football in America did the opposite of what it decided after JFK was assassinated - it would not play.

The SEC followed quickly after.

“Thursday, they reversed the decision, and said we were not going to play the games. There definitely was a change of heart overnight,” Felton said.

Games that would have bearing on who would win each SEC division - Florida-Tennessee and Auburn-LSU - were postponed.

“The deciding factor in delaying the games was the decision made by all the other college conferences and the NFL to not play,” the SEC’s Womack said. “The SEC had made a decision to play at one point based on the information we were receiving at the time and later decided to delay based on the decision of the NFL and other major college conferences. There was constant communication with the Conference office, and the SEC Presidents and Athletics Directors before the final decisions.”

“I think the right decision was made,” Edwards said looking back.

“When the decision was made not to play, I don’t think there was anyone who didn’t understand why,” Stinchcomb said, but he wondered if that would be the final game postponed or canceled. “Once you cancel one game, I think it opens the thought to canceling the rest of the games, but I think that was probably a fleeting thought for me. We have to play right?”

That decision had been made, but there were still lots of questions lingering.

“From a football standpoint, after the games were canceled it was like: 'Well, when can we play the game? When can Florida and Tennessee play their game?' There was a lot of schedule shuffling going on,” Felton said of the time after the SEC made the decision not to play.

“We had a feeling that everything was going to shut down for a while,” Richt said of the moment.

He was right - Georgia would have to wait until the weekend of September 29th to play again. That game would be against Arkansas.

That move had major ramifications years later. D.J. Shockley never played in the 2001 season. By redshirting, he was eligible to play in 2005.

“When we didn’t play that week, we went right into conference play after that,” Richt said. “Because we didn’t play Houston that week, we didn’t play Shockley. When we got into SEC play, we started changing more towards redshirting him. If he had played in that game - back then your redshirt would be gone.”

Four years later Shockley got his first career start against Boise State. He guided Georgia to the SEC Championship Game against LSU.

“Because he redshirted and stayed, he was the starting quarterback in 2005, and was the MVP of the SEC Championship Game,” Richt said.

“AMERICA MUST NOW RISE”

Field Street, which runs along with the Sanford Stadium’s south stands, had been the tailgating and parking home for UGA ticket holders for decades. That’s no longer the case. Television trucks that once stacked up close to Sanford Stadium now rest outside of the edge of the stadium rather than in the shadow of it.

Massive metal barricades rise from East Campus Road near the entrance where the visiting team enters the stadium. None of those things were in place at the start of the 2001 season. They have been a mainstay in Athens for nearly two decades now.

Security at stadiums that hold as many spectators as Sanford Stadium could be targets for terrorists now. Precautions had to be taken to be certain an attack could be thwarted or reduced.

The night of Georgia’s game with Arkansas saw a full stadium with fans eager to cheer on their team, but also to honor America. Before the game, Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA” played as both the Hogs and Dawgs lined up on the hash marks of the field to hold hands.

“It was a little emotional because I can remember before the game them playing that song,” Edwards said. “That was touching. I was a different feeling playing against Arkansas.”

It was hard to not get emotional, but Georgia’s players and coaches still had to figure out how to win.

“I remember Arkansas ran an unconventional defense where they hid a linebacker in the middle,” Stinchcomb said. “We were struggling - having to think of different ways to get to him.”

But even while the game was going on players wondered if an attack could happen in Athens.

“The next thought was it is a huge sporting event. You talk about what is an attention-getter? You bring down a tower. What is another attention-getter? You go to American’s pastime, which is football, and there is an incident? That sends a statement,” Stinchcomb said. “That thought was not far from any of us. It was certainly in the back of my mind, and I was not alone.”

“I didn’t feel afraid,” Edwards said. “There were thoughts in people’s heads like: ‘Man, is something going to happen? There are 93,000 people in here.’ But New York did feel so far away. I guess I felt that nothing was going to happen to us.”

The crowd had settled into their seats, and it was time to get back to as close to normal as possible.

“Now get the picture,” Larry Munson exclaimed from his radio booth. “Arkansas is all in white - white tops, white bottoms with kind of a maroon or garnet helmet and coloring numbers and trim like South Carolina. Dawgs in red and the silver…”

Football was back in Athens.

Edwards was trying to make amends for his performance against Carolina from three weeks before. Finally getting the chance to play gave him a shot at redemption.

“That South Carolina game was probably the worst game I had played in my entire career,” he said. “I think I dropped three that game - the touchdown and two others. It was a bad taste in my mouth, and then 9/11 happened.”

Georgia clung to a 20-13 lead over Arkansas heading into the locker room. By that time, twilight was setting in on Sanford Stadium. A red-soaked sunset sky was giving way to nighttime, and the massive American flag in the corner of the bridge end zone was at half-staff tickling the trees near the bridge on Sanford Drive.

President George W. Bush had ordered all flags to half-staff until Sunday, September 16. He then amended Proclamation 7461 to have flags to half-staff until Saturday, September 22. But Georgia had not played at home. It had not gotten the chance to raise the flag. So, at halftime of the game, Georgia’s redcoat band lined up on the field in a giant “USA” formation, and workers lifted the flag.

Tom Jackson, the public address announcer for the Redcoat Band, spoke to the crowd at the half.

“Though the sorrow that has been brought will always be remembered, America must now rise. Our eyes must rise to meet the challenge of defending freedom. Our cities must rise, bigger, stronger and more defiant than ever of those who disrupt liberty. Our people must rise as the cause of our defense will be great. And our flag, which has hung at half-staff for 18 days, must now also rise. Please stand and honor the symbol of our nation as the American flags of Sanford Stadium are returned to full staff.”

Chants of USA! USA! USA! rang out in the crowd.

The Redcoat Band struck up Stars and Stripes Forever.

In the third quarter, Musa Smith dove into the end zone over the right side of the line to score from two yards out. Georgia was up 27-20, but Edwards would have to make a big play to help the Dawgs seal the deal.

UGA was at the Arkansas 44-yard line. Facing a 4th-and-one situation, quarterback David Greene fumbled, and then picked up the ball to run for seven yards. The next play Greene hit Edwards for a 32-yard strike.

"I remember catching a crucial pass late in the game - great catch over the middle. I got the wind knocked out of me. Randy McMichael jumped on me. I couldn’t breathe, but I had a better day than I did against South Carolina,” Edwards remembered.

Two plays later McMichael scored to make the final 34-23 Georgia. A trip to Tennessee was next. Georgia had not won in Knoxville since Herschel Walker’s first college football game in 1980.

The game is memorable for Munson’s Hobnail Boot call, and Greene finding Haynes in the end zone for the shocking score. After the massive upset, Haynes was getting phone calls all night long - including one from his aunt Audrey, who had somehow made it out of the World Trade Center alive on 9/11.

“She called and said she saw what happened. She saw the play,” Haynes said. “She was real happy for me. She said the world shook when I caught it.”

This time in a good way.

*DawgPost.com has teamed up with Fanatics to connect our readers with the best selection of officially licensed UGA fan gear out there. If you purchase through our links, we will earn a commission that will support the work we do on this site.